|

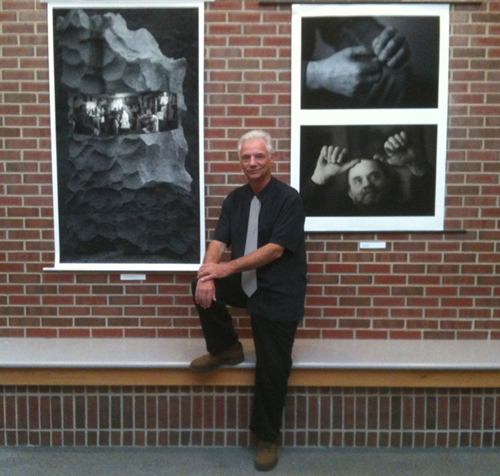

Article published Sep 8, 2008 in the Times Argus Leslie Bartlett has turned the scarred hillsides of Vermont's granite quarries into works of art, the hands of Vermont's stone sculptors into photographs of shadow and light. Generations have worked the quarries, laboring inside the steep walls streaked with light and dark granite, but perhaps never noticed the dramatic striations, slashes of rust or hints of green from the occasional hardy pine clinging to stone. They have missed the art that surrounds them every day, Bartlett fears. "Generations have played, walked and worked here … and seen none of it … the sheer depth and drama of the quarries." Bartlett said last week, standing in the Vermont Granite Museum in Barre before a striking photograph of the Wells-Lamson quarry. Bartlett specializes in natural stone photography, having published a small book of photographs titled "Chapters on a Quarry Wall" – the shots almost look like oil paintings — of the Cape Ann quarries in Massachusetts, set on the ocean near his home in Gloucester, Mass. Those quarries closed in the 1930s; their walls offer more color because of the plant life and lichens that now cover the walls, while the Barre quarries look, at a quick glance, more black, gray and white. Look closer at the Barre walls, however, as captured in one vertical shot by Bartlett, and you'll notice the lines of green and blue stone snaking down the walls, almost undulating. Or the slashes in the granite cut at some past moment by a derrick. Or the russet color fluidly running down the gray walls from what appears to be rusted metal braces in the rock. Bartlett said he first began viewing quarry walls near his home from left to right, then noticed the striations, and finally began seeing the whole scene as a still-life. "It becomes a conversation," he said of the complexity of the gripping quarry vistas. It's about an intimate expression of the heart." The quarry images create a sense of "quiet, a deep quiet," he added. Clearly, Bartlett is moved by quarry walls. But he is equally intrigued with the artists who work the stone, planning a new book of photographs of the hands of the Barre-area stone sculptors. On display last week were shadowy photographs of the hands of sculptor Eric Oberg, hands softer in appearance than you might imagine on a stone worker, the thumb indented from a hammer smash. "They get a show, they get a commission, they are intimately connected to it, and then they let it go," Bartlett said of the granite sculptors. "The focus to me of the stone carvers are their hands." In some ways, Bartlett's affinity for the granite industry is understandable. He lives in Gloucester, a struggling community whose economy has been precariously built upon the fishing industry (you might remember Gloucester as the hometown of the ill-fated fishermen featured in "A Perfect Storm"). Next door to Gloucester is Rockport, an upscale community with shops and inns that cater to the tourists. Gloucester is somewhat like Barre, whose economy has been built upon the struggling granite industry, surrounded by the upscale tourist communities of Vermont. Bartlett is at home with the laboring economies of both, and has artistically adopted the world of granite. Central Vermont's granite industry is, indeed, a part of this community's heritage, culture and employment to be treasured. Every time I visit the Vermont Granite Museum, I am in awe of the work of the men and women who have brought out the stone, and then turned Vermont's famous hard granite into useful structure or artistic beauty. This weekend's Barre Granite Festival (which gets underway Saturday at 10 a.m. at the Vermont Granite Museum and Stone Arts School) offers a much-needed opportunity to cheer this industry – to say thanks to the people who keep the quarries alive and who put the granite to practical or artistic use. Bartlett's work doesn't glorify this industry. The quarry walls in his photographs are scarred, the thumb of the sculptor smashed. His photographs do remind us, however, of the fragility of this stone that supports our communities, which – unless we protect and support it – could become a lost art. Celebrating granite has never been more important. |